Camp, kitsch, retro… How can we distinguish between them? Today we are going deeper into camp with Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp”, a manifesto about this feeling with roots in the 18th century and which is having its moment right now.

Right now, camp is more fashionable than ever. It’s all anybody has talked about since the 2019 Met Gala. But doesn’t being fashionable go against everything that camp stands for? We consulted Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” (1964) to try to explain what camp is and how it extends far beyond fashion.

Camp: notes on fashion

The camp feeling comes from the love affair between artifice and exaggeration and is seen mostly in the visual arts: furniture, decorative arts, cinema, and fashion. The latter is considered one of the most developed forms of visual art, and the exhibition “Camp: notes on fashion” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York makes fashion its central focus to try and explain what camp consists of.

Notes on camp is the framework for the exhibition, which examines how the characteristic elements of this feeling, such as irony, humour, parody, pastiche, artifice, theatricality, and exaggeration, are expressed. Susan Sontag pinpoints the 18th century as the origin of this taste for excess, which was at the time represented by gothic novels, chinoiseries, caricature, and artificial ruins, among other things.

Camp or the spirit of extravagance

According to Wikipedia, the term “camp” comes from the French se camper, which means to pose in an exaggerated way. Moliére was the first to use it to refer to a comic or theatrical act. Sontag points to another dramaturg, the extravagant Oscar Wilde, as one of the main “conscious ideologists” of this concept.

Susan Sontag defines camp as “the spirit of extravagance”. It’s not about bad taste, but rather camp “turns its back on the good-bad axis of ordinary aesthetic judgment”. It doesn’t say that bad is good or that ugly is beautiful, but rather it offers a collection of different rules for art and life. Camp is the victory of style over content, of aesthetic over morality.

In her manifesto, Sontag explains the nuances of this particular feeling that makes the serious frivolous. For Sontag, the most pure examples of camp are the involuntary ones, those of failed seriousness. Camp can only be absolutely naïve or completely conscious, exaggeratedly deliberate as it was with Wilde. Other examples provided by Sontag are diverse and include Greta Garbo, Bellini’s operas, Flash Gordon comics, and Japanese science fiction films.

Camp, kitsch, or retro?

We are much more familiar with kitsch, but in reality we often use it incorrectly to refer to something that is actually camp. The fundamental difference is that, when we call something kitsch, there is a certain element of disdain implied. However, camp reclaims the forgotten by attaching irony to it. It’s not that it thinks bad is good, it’s that it measures these things using a different yardstick. Camp appreciates the vulgarity of kitsch and has fun with it.

Many of the objects that camp appreciates are démodé. Does that mean retro is camp? No, because it’s not about loving old things just because they are old. What happens is that the process of aging has provided the necessary distance for us to be able to can delight in the failure of the attempt. This provokes a campy charm.

Camp in architecture: bizzarro novelty

Brown Derby restaurant on Sunset Boulevard is in the shape of a derby cowboy hat to attract the attention of passers-by. It’s a brilliant example of novelty architecture in which the buildings take on unusual forms for marketing purposes, or just to attract attention. They might imitate objects or other buildings, but without wanting to achieve credibility. Rather, they are just buildings that imitate other things. This bizarre architecture can be included in camp because of the exaggeration and, above all, because of its humour. This is evident for those looking at these buildings, even if it is not in the spirit of the architect that designed them. Camp is playful and wants to do away with the serious, and what’s more serious than architecture?

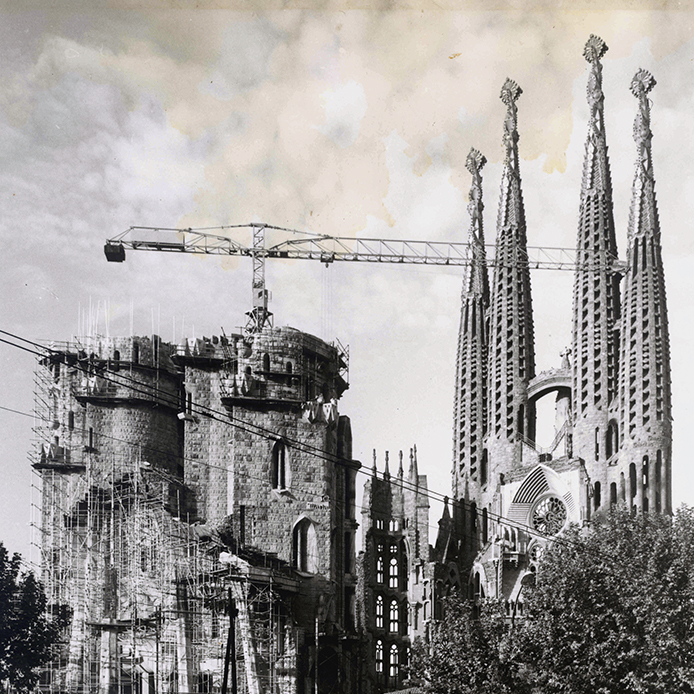

Was Gaudí camp?

If Camp is failed seriousness with the right mix of exaggeration, fantasy, passion, and ingenuity, a good example of involuntary camp would be the architecture of Gaudí. For Sontag, it’s camp because it is fantastical and ornamented, but also because it reveals the somewhat excessive ambition of a passionate architect who foolishly believed that he alone could come up with an entire culture. The unfinished Sagrada Familia is testament to this excessiveness.

Camp in the decorative arts

One of the fields in which camp is most present is in the decorative arts. The excess and mannerisms of camp are embodied by decorative objects and interiors where artifice dominates. This is the case with art nouveau, which for Sontag is one of the most camp styles. Creations from this movement play with the idea of turning one thing into another, such as the exits of the Paris metro by Hèctor Guimard which are in the shape of an orchid stem, Tiffany lamps that want to be flowering plants, and grotto furniture.

From Batman to Cher

Given its preference for the visual arts, we could probably all provide campy examples from cinema and television. Looking back, we see television series from the 1960s, inspired by comics and defined by bright colours, that weren’t intending to be camp, but whose campiness we enjoy today. These include Batman, The Addams Family, or Gilligan’s Island. The same thing happened with soap operas like Dallas and Dynasty and their cardboard cut-out luxury. However, there are also camp filmmakers that consciously translated this feeling to their films, such as John Waters. Pink Flamingos and Divine are the height of camp, which also embraces the marginal.

We can see traces of camp in music in everything from variety shows to cabaret, in excessive stars like Liberace, Elvis in his later years, or in contemporary divas like Cher and Lady Gaga. Las Vegas, with all its bright lights, could be considered the camp capital.