How do you build in Africa, for Africa? At Connections by Finsa, we wanted to put together a snapshot of the current landscape of new architecture that’s popping up all over the continent by taking a closer look at some of its movers and shakers:

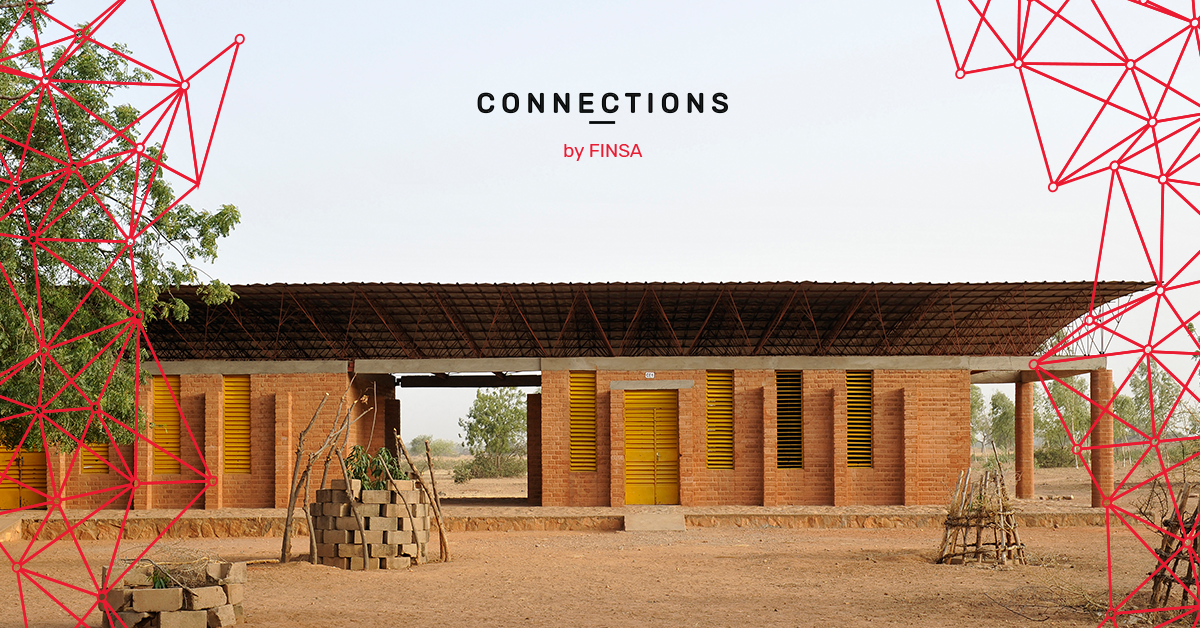

Francis Kéré (Burkina Faso)

The simple primary school that Kéré built in Gando, which was initially intended for 150 children, eventually developed into a set of buildings used by approximately 700 children and teens. His later projects in his hometown included lodgings for teachers, a community centre, and a library. He prioritised the local definition of comfort in all of these buildings, using materials and structures that allow warm air to escape, with high, sloping ceilings that act as air chambers, lengthening them with cantilevers that provide shade outside. Kéré also helped to empower rural communities by involving the people of his village in the project.

The school:

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

The library:

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

Another of his projects was the new design for the National Assembly of Benin, a 35,000 square metre space that has been in development since 2018. It will be home to the Parliament of the country, situated between Togo and Nigeria, and is inspired by the palaver tree, an ancient West African tradition in which people gather under a tree to make decisions on behalf of the community.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

David Adjaye (Tanzania)

The National Cathedral of Ghana, the new cathedral in the capital of Accra, is a real challenge because of Adjaye’s ties to the country (his parents were from Ghana), as well as the proportions and unique characteristics of the structure. The avant-garde style building is both a religious institution and cultural entity, in addition to acting as a community centre. It features several chapels, a baptistery, a music school, an art gallery, an auditorium that can seat 5,000 people, and the first Bible museum in Africa. The structure is unique thanks to its pitched roofs and its eye-catching concave front elevation. Adjaye also collaborated with local artists and artisans to decorate the religious spaces inside the cathedral.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

Another challenge for Adjaye was the design and construction of 101 new hospitals across Ghana. For this project, he focused on the idea of a hospital as more than a place where you just receive medical attention. The structures are sustainable, efficient, and designed for the community, with green spaces that promote wellbeing and healing. The goal is to provide an excellent and cutting-edge hospital experience. Each of the facilities covers 8,500 square metres and features a series of single-storey blocks. The design was inspired by denkyem, which symbolises a crocodile, a creature that can live on land or in water. This is why each of the hospitals will have a similar structure but will adapt to the characteristics of each location. Patient rooms will have butterfly roofs to maximise natural light and cross-ventilation, while areas in which surgery will take place will have more controlled features, with gable roofs that have long cantilevers to protect them from the sun. Both types of roofs will collect rainwater. Locally-made earthen bricks will be used for the building envelope. Few imported materials will be used, thus reducing the project’s carbon footprint.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

Kunlé Adeyemi (Nigeria)

The founder of NLÉ Architects is known for being the creator of the Makoko Floating school, a prototype prefab structure built on water for the Makoko community, a slum sitting on piles. Located in Lagos, Nigeria’s most populated city, it’s also one of the biggest settlements in the world. The construction project took on an innovative approach in order to meet the social and physical needs of the people in the face of climate change. In fact, Adeyemi’s main objective was to create alternative construction systems that are sustainable and environmentally friendly. The Makoko school is basically a wooden frame that floats on plastic barrels which help to avoid flooding. It’s quite flexible and can act as many different things: a school, a community centre, a concert hall, or an exhibition space. It’s a practical solution for rugged conditions that Adeyemi has used in other places all around the world, including Venice, Bruges, China, and Cape Verde.

Mariam Kamara (Niger)

“How can we use architecture as a tool to create more democratic public and civic spaces in the cities of the future? When our globalised context is resulting in the creation uniform images across the planet, how can buildings honour a specific cultural and historical context, its geography, its climate, but look decidedly towards the future?” This is the philosophy of Mariam Kamara, and she applied it to the Cultural Centre of Niamey in the capital of her home country, Niger. She designed it with the help of David Adjaye and the patronage of Rolex. The structure she came up with fills, as she said, a void in a city that has very few cultural meeting places and points of sale. “And that’s the most important thing,” she says, “to provide a place to learn, to dream”. The concept comes from traditional architecture and highlights bioclimatic solutions and sustainable practices such as using local materials, collecting rainwater, and using solar energy. It was designed to be an integral part of the city, a natural meeting place that is accessible to all.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

Another of Kamara’s projects in the sustainable-design-as-a-social-value realm is the Bët-bi museum in Senegal. For Kamara, sustainability doesn’t begin and end with installing some solar panels or using natural local materials. It’s a concept that goes beyond that and that is intertwined with culture, memory, and community.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

MASS Group (Rwanda)

The redesigned Ruhehe Primary School, located in the northern Rwandan district of Musanza, is an example of the vision that this group, which is made up of more than 250 architects, landscape designers, engineers, furniture designers, creators, writers, film makers, and researchers, has regarding the impact of architecture on people’s lives. MASS is convinced that architecture is more than just buildings and that it has a fundamental role to play when it comes to helping communities deal with their history and plan for the future with the new possibilities it holds. The new Ruhehe school, which has more than 1,000 students enrolled from preschool to sixth grade, was designed in the shape of a necklace, with classrooms hanging like pendants along a chain. These ‘pendants’ are surrounded by a wall that protects students and prevents them from getting distracted. It even has kid-sized doors.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

Sénamé Agbodjinou (Togo)

This architect is also an anthropologist, poet, researcher, and activist. With this multi-faceted career, it’s no wonder that Agbodijnou’s work has many aspects to it. He works on urban projects that empower communities and that feature technology quite heavily. He believes that the cities of tomorrow will be designed and built by their own inhabitants. For many years, Agbodijnou has been running the HubCités Africaines program, with the goal of getting people to take back the power of transforming the places where they live and how they live through learning and collaboration. He wants to build smart cities, not in the Western way, but within African contexts. In an interview with El País a few years, he summarised his view of urban planning in the following way: “I work in vernacular architecture, meaning that I build alongside people”.