Michel Foucault, a 20th-century French philosopher with a significant influence on our view of urbanism and architecture, defined the garden as a microcosm containing the entire cosmos; the projection of our society and our desires in a condensed context. Leveraging the Garden Futures. Designing with Nature exhibition, which took place at the Vitra Design Museum during 2023, we explore the essential coexistence of nature and city.

Designing with nature

Viviane Stappmanns, Nina Steinmüller, Marten Kuijpers, and Maria Heinrich, the curatorial team of the exhibition, are aware of the symbolism of gardens and have studied the history of this urban element in relation to different eras and societies. They also interpret its potential within concepts such as social justice, biodiversity, sustainability, and the recent rise of urban gardens.

The exhibition, designed by the Italian team FormaFantasma, begins with a multimedia installation where we will enjoy works by architects and designers of the caliber of Alvar Aalto and Luis Barragán. Here we perceive the symbolism Foucault spoke of, the garden as a place to project our dreams, a refuge from the everyday.

The garden as a reflection of history

According to the curatorial team, despite the symbolic load, green areas reflect the historical circumstances of each era. In the second part of this exhibition project, the colonial past of Western gardens is evident. Additionally, innovations that allowed the introduction of exotic plants are explained. The Wardian case (invented in the 18th century and widely used during the 19th century) is a good example. It is a glass box that allowed the transport of plants over long distances; it favored the exchange of beneficial specimens (rubber or tea), but was also responsible for the spread of invasive species.

Possible green utopias

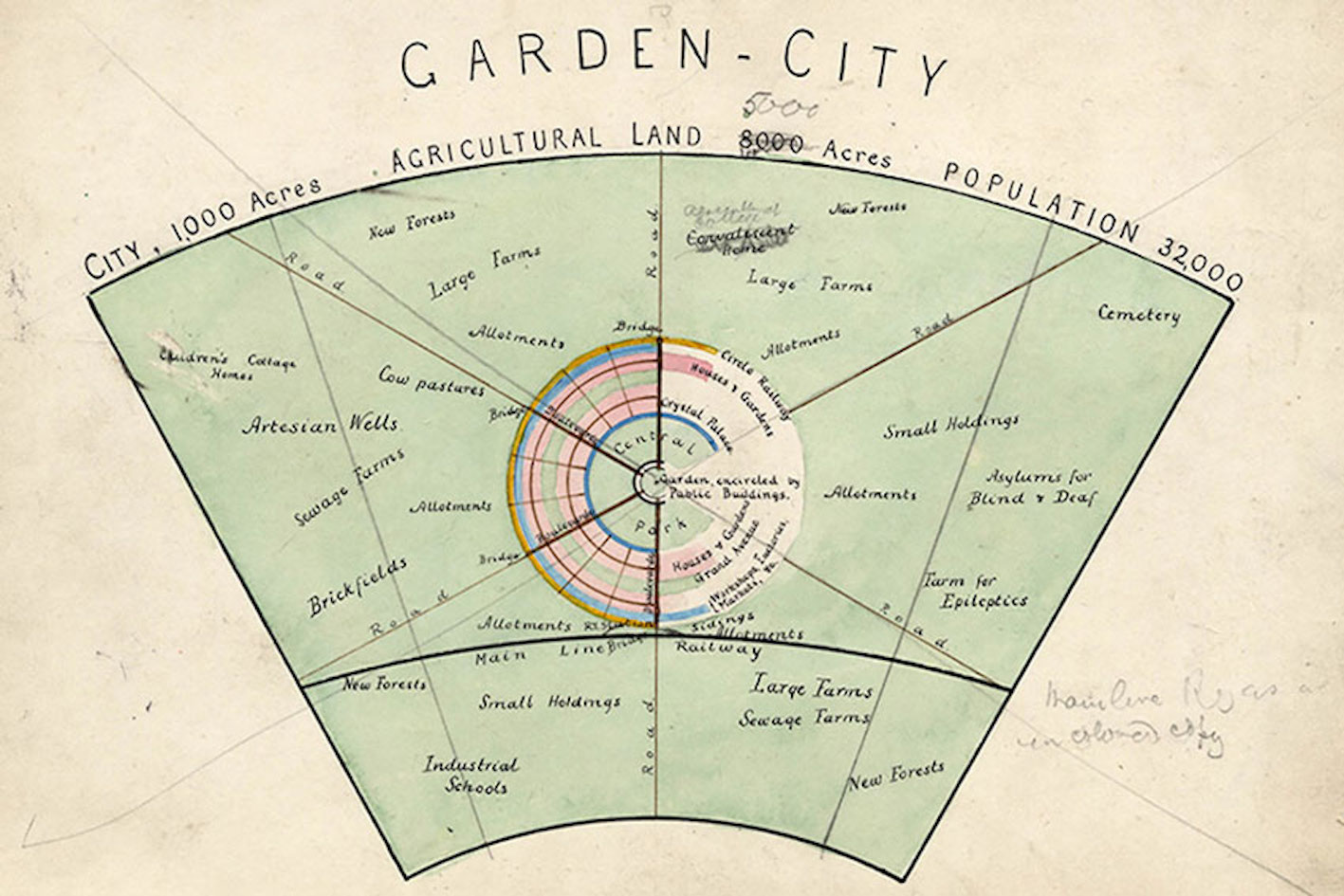

In the 19th century, other urban projects with very different objectives emerged, reflected in these rooms. Ebenezer Howard, bordering on utopia, designed a garden city capable of providing food to all social classes. Green Guerrilla, in 1970s New York, defended urban gardens as a social tool and for citizen participation.

Revisiting the past

As a retrospective, Garden Futures presented nine garden designs from the early 20th century to the present. There isn’t a search for exoticism, but rather a review of that colonial past. For example, Burle Marx, influenced by avant-garde trends, created a garden with abstract shapes from native plants of Brazil. Malaysian Ng Sek San, on the other hand, cultivated a community garden in Kuala Lumpur that served as an example for similar initiatives.

The future of gardens

Where have gardens evolved to today? What can we learn from their planning? Is it possible to extrapolate it to other design areas? Viviane Stappmanns gives us the key in this interview, reminding us of the words of musician and composer Brian Eno: “Think like a gardener, not like an architect: start the design, but don’t finish it”. Gardens allow a balance between planning and organic growth: this forces us to improvise solutions that adapt to each problem.

Bio-design: a collaboration with nature

A good example of this adaptation is Gavin Munro. This bio-designer, whom we have already discussed in Connections by Finsa, constructs furniture with living plants, manipulating their growth until achieving the desired shape. Invited to a conference on the occasion of the exhibition, he explained how the key is not to force nature, since only by collaborating with it will we achieve the desired goal.

If Munro creates furniture, Ferdinand Ludwig takes it a step further with a new construction technique: Baubotanik. This doctor of architecture has developed a line of research in which he erects habitable structures from certain trees and various processes such as pruning or grafting. It is not an innovative idea, if we think, for example, of the living root bridges in Meghalaya, but Ludwig goes a step further by incorporating metal scaffolds and other materials that will merge with the tree over time. Through this method, Ludwig manages to take over a space that has belonged to architecture for centuries and thus break the tension often present in our relationship with the natural environment.

Vertical gardens

Another way to break this friction between architecture and nature is the planting of vertical gardens. Meadow, by Alexandra Kehayoglou, stands on one of the walls of the Vitra Museum. It resembles a miniature meadow, but it is actually a carpet made of wool and remnants from a factory’s materials.

The first vertical garden was erected by Patrick Blanc at the City of Science and Industry in Paris, in 1988. It is an increasingly used resource, since, apart from its obvious beauty, it improves the quality of life on the streets where it is implemented.

One of the most impressive vertical gardens can be found in a private house in Linkebeek, Belgium. Conceived by Samyn and Partners Architect in collaboration with Patrick Blanc, this facade features a selection of exotic plants that give it a striking appearance.

There are even indoor vertical gardens, like the one at Edmonton International Airport in Alberta, Canada. At 132 meters, it is the largest one ever built in an airport terminal.

For the construction of these vertical facades, specialized and high-quality products are necessary to ensure the stability of these structures. With this goal in mind, Finsa has developed a solution for durable wood facade cladding, free of toxins, with low environmental impact and sustainable: Thermopine. This emerges from a collaboration between Savia (integrated into Finsa and focused on the transformation of solid wood) and Verde Profilo, a company specialized in the design of vertical gardens; this results in a wide catalog with numerous alternatives for their construction.

Urban gardens

When we talk about the attempt to bring greenery into our cities, the proliferation of urban gardens has been one of the most visible phenomena in recent years.

In an attempt to reclaim Ebenezer Howard’s utopia, or the meeting place proposed by the Green Guerrilla, our cities are filled with small plantations, which supply food and an unexpected habitat for biodiversity.

La Finca del Sur, in the Bronx, New York, is an initiative led by black and Latina women that promotes economic independence, food justice, and education. Since 2009, it has not only provided the community with organic and affordable products but also a place for political and community meetings.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

Since 2010, Fresh & Local has been transforming underutilized urban spaces into productive farms with the aim of improving the health and well-being of Mumbai’s residents, the second most populous city in India. Here, workshops and activities on agriculture and sustainable food production are held, as well as an urban gardening program: The Nomadic Garden.

All these solutions create small green oases in our cities. It’s interesting to end with a reflection from Viviane Stappmanns. She wonders if perhaps gardens are no longer places where we shelter from nature but, instead, spaces where we protect nature from people, safeguarding it from the impact of our actions. They are, Marten Kuijpers reminds us, places of learning, possibilities for a better future in which the human species is not the undisputed center, but rather a part of a vast ecosystem.