In August, we will once again look at the sky with the attention it deserves. It will be the peak of the Perseid meteor shower, also known as the Tears of Saint Lawrence, one of the most spectacular events in our celestial vault. Astronomical observatories are the result of a continually evolving structure built for the study of the cosmos. We will explain their evolution up to the present day, what factors have influenced them, and what types are most representative of each era.

What is an astronomical observatory?

Although the evidence is not definitive, it seems that ancient civilizations such as the Egyptians, Babylonians, Chinese, and Mayans analyzed the universe through certain constructions. Some prehistoric structures were designed considering the sunrise and sunset, which would facilitate the measurement of time and, consequently, the creation of calendars. They thus become key pieces in the organization of crops and, therefore, economic control. Stonehenge (3100 BC) or the Mnajdra Temple (3000 BC) are simple constructions with low levels of technology, which is compatible with a nomadic population. Another of their most notable characteristics is their monumental size, which has also allowed them to survive to this day.

The beginnings: proto-observatories

Egypt, Babylon, China, and the Mayan civilization were the first societies to develop places from which to observe the stars. They were able to predict eclipses and catalog stars and constellations. Their structures were limited to the alignment of architectural elements with celestial bodies. Although their purpose is not proven, it is believed that they allowed the measurement of time and the creation of calendars. These constructions would be of great help in optimizing agricultural cycles and thus facilitating economic control.

We are not as fortunate with later, more complex civilizations, from which we have not inherited remains. Mesopotamia, for example, had large constructive groupings. Because observation instruments were simple and did not require a specific structure, any clear, high place could be used as an observation platform. Although it is not scientifically proven, it is believed that ziggurats may have been built for this purpose.

Islamic culture: the emergence of the institution – Permanent and specialized spaces

The Greek civilization made significant advances in astronomical knowledge. Aware of its usefulness for navigation and time measurement, they focused their investigations on the movement of planets, the sun, and the moon, and the cataloging of constellations, which were associated with the worship of some gods. Although we do not have evidence of buildings solely for observation, we know that graduated instruments, essential for the advancement of this science, were developed during the Hellenistic period.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Islamic culture preserved the astronomical knowledge achieved by the Greeks. They became aware of the temporal scale needed for these studies, leading to the first institutions that contemplated continuous monitoring over time. This change involved permanent spaces, a workforce that was renewed over different generations, and patronage that made it possible. The Maragheh Observatory (1259) is considered one of the best examples. More than for the relevance of its investigations, this building was vital for the transmission of knowledge.

The large number of students and assistants who participated in observations, as well as the gradual increase in the size of the instruments, determined the design of these constructions. The observatory thus becomes a complex of buildings with differentiated functions, marking the emergence of the typology as we understand it today.

Modern observatory: technical innovations define architecture

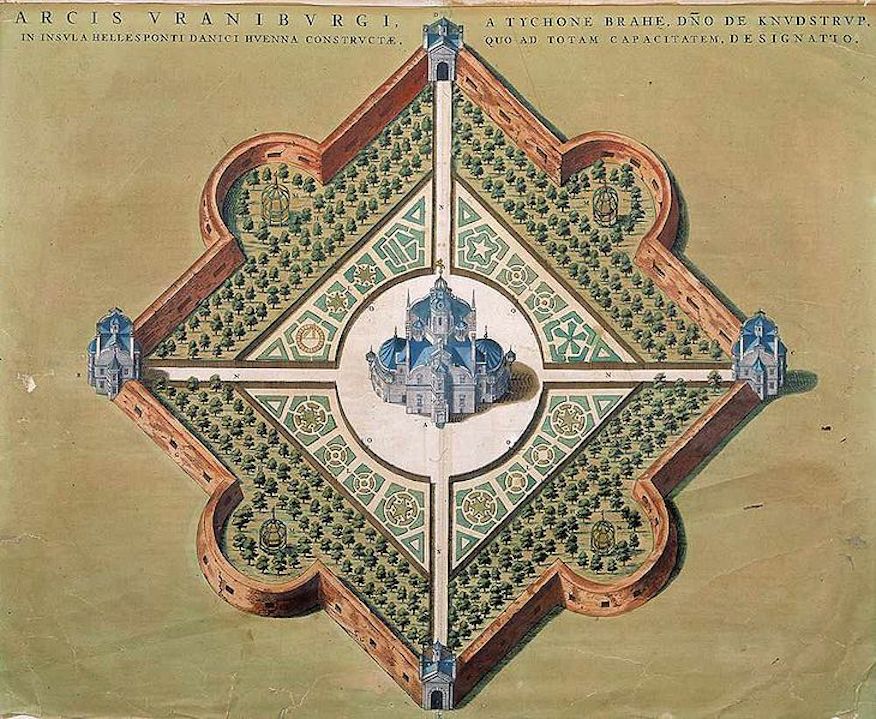

Tycho Brahe, a Danish astronomer and main responsible for the Uraniborg Observatory (1580), the prototype of the modern observatory, pointed out in one of the chapters of his work Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica the relationships between architecture and astronomy that would define the typology of this era. The most characteristic feature of this period is the adaptation of architectural design to observation instruments and their functions. Architecture increasingly submits to practical needs and the increase in the size of various elements. For Brahe, the suitability of the location was key. This included the need for elevated surfaces and a favorable geographical location in terms of light and climate to facilitate data recording.

The Danish scientist prioritized functionality over aesthetic issues. He was aware that technical innovations and instruments would guide these constructions, which was demonstrated in subsequent designs. Uraniborg had considered scientific issues and had several platforms for observing the sky from all angles, but the continuous movement of instruments between different platforms complicated many investigations.

The telescope: a turning point

The telescope, which emerged in the early 17th century, allowed its use from balconies or windows due to its small size. Observatories were built at this point with very simple structures, or small platforms were added to place the new instrument.

In the mid-17th century, a competition began to obtain the most powerful telescope. This translated into more length, to the point that they no longer fit in many buildings. As a result, observations were moved to the open field, often far from the observatory itself, leading to practical problems when analyzing results. The Greenwich Observatory (1675), designed with these new variables in mind, reserves a prominent place for the telescope: a large octagonal room with large windows in all directions.

18th and 19th centuries: expansion and scientific dissemination

During the 18th and 19th centuries, astronomical observatories expanded across all continents, incorporating technical advances achieved up to that time. Some of their characteristics are the separation of rooms for different uses, alignment with the cardinal points, and a progressive abandonment of the city.

These buildings tend towards horizontality and are of low height; they are topped with movable domes where the telescope, now the protagonist, is located. As for the rest of the rooms, they do not have representative elements, as they are intended for uses with fewer requirements, such as study, teaching, or rest.

Astronomy reached widespread interest during this period, leading to societies of amateur astronomers and observatories functioning as centers for scientific dissemination. The Griffith Observatory (1935), one of the most recognizable buildings in Los Angeles, is an example of this.

What is the future of observatories?

In recent decades, observatories have shed all unnecessary ornamentation to focus on ensuring precision. Another consequence of technical advances is the reduction and decentralization of human teams. Due to this, habitable space has been minimized in these constructions. This feature does not mean the disappearance of the typology; on the contrary, it is a logical evolution leading to space satellites and interventions in the landscape close to land art.

We live in a time when new spatial possibilities are opening up: it is not just about observing the cosmos but also about recreating it. The Super-Kamiokande (1996) in Japan, located one kilometer underground, is a large water tank 40 meters in diameter and 40 meters high. Built to capture subatomic particles from the sun (solar neutrinos), this artificial architecture represents another step in an increasingly varied characterization. Not only do satellites show us the cosmos like never before, but also the simulation of spaces within our planet can paradoxically bring us closer to the stars..

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

If you enjoyed this historical journey through the architecture of observatories, don’t miss this selection of four observatories of singular beauty.