Ricardo Tubío and Xabier Rilo are industrial designers. Together they make up Cenlitrosmetrocadrado, a studio with a humanistic focus that approaches every aspect of design – the practical, the emotional, the social – from a functional perspective. Product design, spatial design, graphic design – there’s almost nothing they haven’t done.

Which fields do you feel more comfortable working with at Cenlitrosmetrocadrado?

At Cenlitrosmetrocadrado, we accept jobs that are very different from each other, because we believe that design covers many disciplines and can provide solutions to diverse problems independent of their origin, and the approach for each problem is very similar.

We put everything through the filter of product design because it’s an area that we feel comfortable [working] in and it defines the way we work. In graphic design, we try to transmit this ‘object’ aspect by developing three-dimensional concepts or through volumetry. When designing spaces, we create them by starting with the furniture, making sure all the objects that emerge during the project are in harmony with each other and that the story is told by what’s inside the space, not the container [i.e. the space itself].

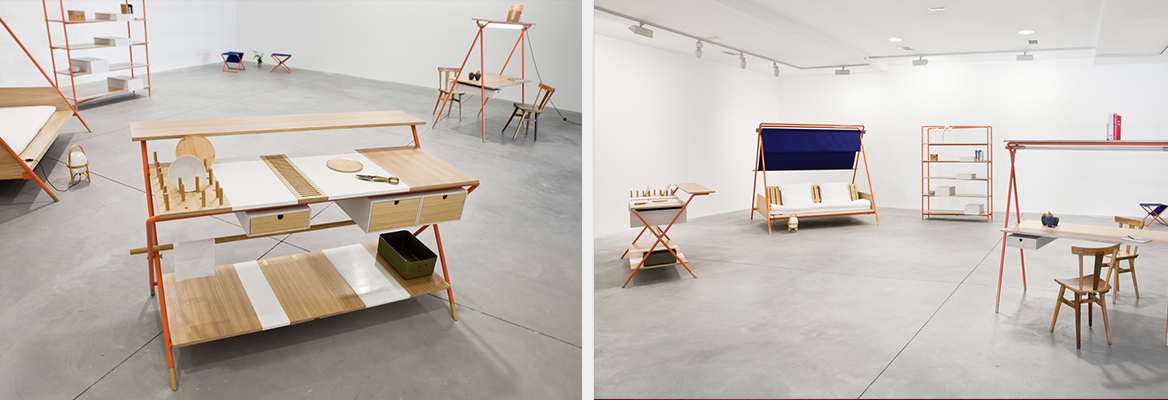

The way we understand a space has materialised in Extenta, the furnishings for Cuarto Pexigo, an artist’s residency : it was created by starting with multifunctional furniture pieces that are in this “container” [the space] but which could also be in any another, and the space would still be the same. It’s about generating all of possible uses while using as few pieces as possible and providing solutions in both the domestic and professional realms. It’s a more evolved version of Global Refuge, which included all the basic fundamentals required for living.

Which part of the creative process do you enjoy the most?

Each phase belongs to a continuous process to which they are all relevant. Perhaps the most primitive stage, in which the concept and discourse are generated, is the strongest and it guides the whole process. That part that involves working on the soul of the project is very important in our jobs and it’s what people pick up on.

We always work with two focal points. One is more functional, paying attention to the technical requirements and more objective issues, and the other is more metaphysical, focusing on what the pieces themselves are saying. These two focal points guide us throughout the project while we are defining the final product. That’s why it’s difficult to choose one phase, because in reality you never stop designing: design is a continuous process.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B42AfApHrDZ/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

What would be your dream project?

It’s always the one that you haven’t done yet, but specifically we would like to design a product that is made for more industrialised production. Everything we have designed up until now, bar a few exceptions, have been one-off projects. It’s also true that they arise without the intention of taking it any further, which allows us to work on them in a more artisanal way when it comes to producing them and it also restricts the project. It would be interesting to have a project with more reach, that could get to more people, because at the end of the day what you want is for the product to work for what it was designed for. It takes a lot of effort to make a product as a one-off piece and it could be seen as almost elitist, when what we actually believe the complete opposite: design must be an accessible discipline that is used as a tool to solve society’s specific needs, and the more people it reaches, the better.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B6MBwUbnZfP/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

You are the creators of Global Refuge, an installation that reworked the concept of a home at Casa Decor three years ago. How are you revisiting this project during the coronavirus crisis and lockdown?

The thoughts from which it arose were not that different to the situation we are living in today. We have been working from home for a month and a half and in the end, [you realise that] you keep pieces that help you live the domestic part of your daily life, and that you also need a series of pieces that help you develop your professional side. We had already started doing this in our homes, perhaps due to a professional bias. We try to have homes with as few rooms as possible and in which the pieces are multipurpose and can support various activities.

How important is home nowadays?

It’s very important, if not the most important thing. It is the nucleus, because it’s where you spend the most time and with the people that you choose to spend that time with. It’s an extension of the person, a place where you can feel comfortable because you spend a lot of time there.

What insights have you experienced as a result of the pandemic? How can we reflect on the perception of space?

Our perception hasn’t changed. We try to design rationally so that everything is justified and provides solutions to a series of needs. We don’t leave space for the superfluous or the banal: if it’s there it’s because it has to be there and everything has a function, be it practical or emotional. Then we calibrate how much there is of each one, trying to find a balance in the combination. In the current situation, you realise that there are many superfluous things that don’t contribute anything other than indicating a certain status to others.

A quote that defines the world we live in very well says that we spend our lives working to earn money to buy things that we don’t need and impress people that we don’t care about (Lawrence J. Peter). We believe that the elements in a space must contribute something to it and that they must have a functional, practical, or emotional component to them.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BMqqGDsFZt1/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Who are the designers or creatives that you connect with?

With those whose way of thinking is similar to our own: Tomás Alonso, the Bouroullec brothers, Jasper Morrison, Naoto Fukasawa, professionals that understand that design is a tool that provides an answer to a series of requirements, in which it is the object and not the designer that needs to express itself, as opposed to those who are looking for impact, independent of whether or not the thought behind the project is appropriate.

But we also connect with companies like the Nordic firm Carl Hansen or the Japanese outfits Muji and Maruni, who care a lot about the production process and the workers. Because it is important to realise that it isn’t just the designer that is behind the objects, but also the people who work with the raw materials, those who make the product with love and care.

What are some of your sources of inspiration?

We really like looking back on our own experiences and projects. Despite the fact that we think Galician design doesn’t exist in the same identifiable way as Dutch or Italian design, we believe that living here means our work is inspired by those roots and this is transmitted [in our projects], consciously or subconsciously. It’s a way of working, a way of understanding objects…

Tradition, our own experiences, the society that we grew up in, and all the things that surround it, all of it influences the way we design. In the end, inspiration comes from everywhere – [everything] from important creators to the work of a blacksmith. You don’t need a design studio; an artisan can be a designer, because every object that has been created has been designed.

In THIS POST you can enjoy a selection of projects by Cenlitrosmetrocadrado from the fields of product design, spatial design, graphic design, and more.