Flamenco has interested Pedro G. Romero from very early on. This “undisciplined artist”, who already triumphed at the last edition of dOCUMENTA with La farsa monea, a performance with Niño de Elche and the dancer Israel Galván, never stops working. His latest project has been to convert the Alarcón Criado art gallery in Seville into a “Sala de Ensayo” (Rehearsal Room), an open space for flamenco artists and fans, and a place for experiences. Today we’re connecting with him to take a deeper look into his work and his spirit.

Pedro G. Romero with some of the participating artists at the Sala de EnsayoWhat is Sala de Ensayo? How was it born? How do you hope it evolves?

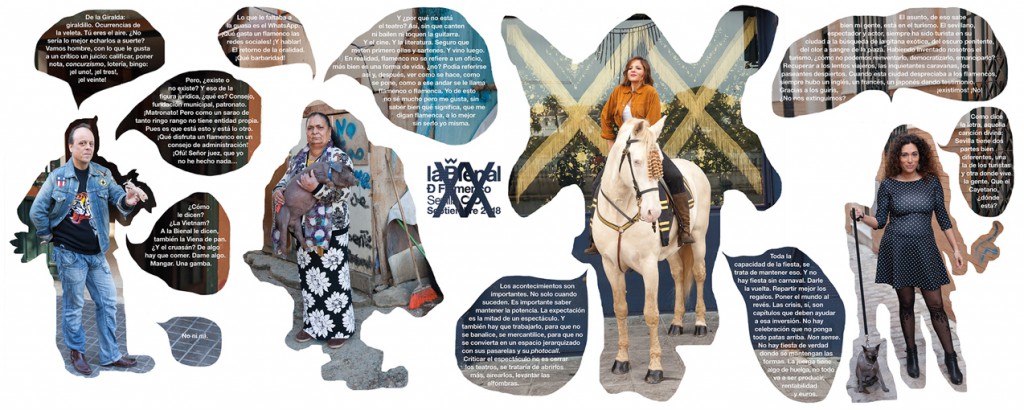

Sala de Ensayo is really an attempt to explain myself and to explain what interests me most in the artistic field that is flamenco and the possible characteristics of my involvement in this field. In some way, the proposal of the Alarcón Criado gallery arose from my involvement in the poster for the XX Bienal de Flamenco. Beyond the issue of taste, the poster was interpreted as very audacious when for me it was an exercise in tradition, of camp art, a mix of the of the Álvarez Quintero Brothers and Samuel Beckett, an attempt to situate certain discourses within a wider field, for the general public, so to speak.

In reality, there are other things about flamenco that interest me: the connection between gestures, body, and language on the very edge of culture, an open relationship which continuously gives us a glimpse of the animal that we are. That happens a lot during rehearsals, in the special space for constant creation that are the flamenco rehearsal. The polysemy of the word ensayo (rehearsal) as a feeling, as a study, but also as a kind of discourse, an examination of things. In some way, that is what we are trying to display on the tablao (flamenco stage) that has been built in the gallery.

What my friends said to me was very interesting: “What a sleek exhibition, Pedro! What changed you?” But that extension of feeling that I always try to give with thousands of papers to read, coins in circulation, things to put in and take out, that blurring of form through the infinite production things, papers, or bits of information…here, all of that is provided by the many wonderful artists together with the curating that I did with Javiera de la Fuente and Marco de Ana, that all work together on the tablao. It’s a very dense work that even overwhelms me. More than seven hours of recording every day over three months. Alarcón Criado is working very hard and we now have to think about how make the whole experience flow, all of this accumulated capital, without betraying the purpose. To see how it can continue to work, above all, as a purposeful space despite becoming an exchange of value. In other words, working out how to “sell” this work decently. Putting these pieces in the value circuit of the market is work that is still ongoing. Because another thing I have learned from flamenco is how to use these tools and the value of money, the use and abuse of value. But that’s a whole other story.

And where did the interest in flamenco which is so obvious in your work come from?

Actually, I’m a privileged fan. Thanks to my friendship with José Manuel Gamboa, my cousin, and José Luis Ortiz Nuevo, my teacher, I ended up having a very privileged relationship with the genre so that, when I started working with Israel Galván in 1998, it also became a field of work for me. And it’s such a rich field and so full of stereotypes that, little by little, its processes and teachings have begun to definitively colonise my work, if you can use such a word for a movement that has its origins in the subordinate. For me, it is a field of continuity. I belong to that which some now refer to as the “cultural classes”, that is the scope of my work. Genealogically, bohemia, then the vanguards and counterculture, are the productive ancestors of this class. Remember that bohemia was a word like flamenco, that referred to “gypsy ways” of living. In France at the end of the 18th century, when the word “bohemia” was born, it was assumed that the gypsies, the Rrom, came from the Bohemia region of the Czech Republic. That means that for me it is also a radical examination of the language that I work with, a way of thinking about what my condition means.

You are often defined as a multidisciplinary artist. What does that word mean to you?

I prefer an undisciplined artist. Basically, I make all kinds of works, but in one way or another they are all tied to what was called fine arts. Francisco de Holanda, a contemporary of Miguel Ángel, insinuates that that “Bellum” has something to do with the “Guerra” (war). It is a crazy etymology, but beauty has always been a battlefield.

Archivo F.X. is about to turn 20. Will it ever close?

Now I work on the project as if it were already closed. I don’t know what that means yet: I’m revising everything I’ve made, cataloguing it, inviting other artists to intervene. I’m working on Archivo F.X. itself, the way that Archivo F.X. worked on the images of iconoclasm and vanguardism, and this operation is providing clarity, precision – everything I could ever want. But the relationship between form and the blurring of form is getting clearer every day. I’m thinking about working on Archivo F.X. in this way, institutionalising it, monumentalising it, enthroning it. I think the effects operating on any work of art have to do with the field of operations, with the nature of our work. What I try to do is control it and give these operations a fit that I think is coherent, so that they don’t deny, to my regret, the lines and basic gestures of this work. I think there is a republican way of enthroning, for example, and that’s what I employ.

It is evident that a lot of research goes into your work. Is it necessary to be a good researcher in order to be a good artist?

You must know the materials you work with well. It is not too different to knowing how to make colours, mix pigments, the patinas of bronze…But nowadays art works with other materials, with knowledge and information, and we must treat it with the same care. I still agree with the old idea of fine arts, when knowing the trade was important and fundamental. Knowing how to choose a good passe-partout was the same as knowing how to choose galleries, fairs, biennales, and institutions to work with today. But the idea is the same, thinking of the best frame for your work. In this sense, when the language of art has extended its reach so much, it is logical that one learns or tries to learn a lot from this expanded field of language that is current contemporary art.

What project do you have in the works? Where do you see your work heading in the future?

As a curator, together with Luis Montiel and Joaquín Vázquez, I’m preparing the Aplicación Murillo in Seville, which is a contemporary reading of the work of Murillo. I am also developing a series of works on the subject of exile, on what we have truly learned from our condition as exiles. They will be seen, in varying degrees, in Córdoba, Málaga, Dessau, Corsica, Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro, Caracas, and Bogotá. At the Bergen Assembly in Norway, we will present a wide array of works on the subject of parties from a political point of view, that joint celebration that both things should be. Basically, I have more work in the future, which isn’t bad at all.

What would be your dream exhibition space?

The thing is I have already been able to show my work at some exceptional places which have been, in some way, very important for the awareness of my own work. In those cases, the place defined the work as important. This happened in Thessaloniki in the mosque that used to be a synagogue for the sabbatianos, followers of Sabbatai Zevi, where I was invited to show my work by Catherine David for her project Heterotopías. In a way, these exhibits in the Iglesia (Church) de La Caridad in Seville have the same range. For example, I would like to do something at the Sanctuary de Congonhas do Campo (Brazil), where the works of Aleijadinho are. Or in the triangle marked by Port Bou, Hondarribia and Colliure. The intellectual horizon that José Bergamin, Walter Benjamin, and Juan de Mairena have given me is priceless.

Process or result – which part of your work do you most enjoy?

Fortunately, it’s something that I resolved years ago by abolishing the differences between them. Projects are never finished, they are abandoned.

How do you connect with what interests you? Are you more digital or analogue?

I don’t really distinguish between the two. For me print and the computer are on a continuum, but nature and culture are also on a continuum. So I don’t differentiate them. This continuum might be a Moebius strip, it’s true, but that’s where we are heading.

How do you disconnect to recharge your batteries so that you can continue your creative work?

I often say that in order to rest after one job I take up another, but that’s probably not true. It’s hard for me to distinguish between work and daily life, as they aren’t separate things for me. In reality, most of the time my work consists of resting, of being idle. Laziness is the main source for my countless endeavours, a contradiction that seems to work well for my body.

If you hadn’t dedicated yourself to art, what do you think you would have ended up doing?

It’s actually such a huge field…In Andalucía, the purpose of art is not confined to fine arts. We still have the old understanding of the word art: to live with art, to live from art, to know the art of living…

Which artist would you like to collaborate with, even if you haven’t done it yet? Who are your inspirations?

I have a lot of inspirations. A thinker with whom I would have liked to work died very recently – Clement Rosset. I would also like to do something with Pepe Habichuela one day, a great guitarist, or I would have liked to work with the Vainica Doble. I think they had a unique and impressive voice. I could almost say that I am working with Teresa Lanceta, but to do something in textiles with her…although perhaps we are also doing that. I really like working with Alejandra Riera and at some point, we might do something more concrete. Raoul Vaneighen, Alice Becker-Ho…

I am lucky to work with many people that I admire, so lucky that I no longer think of it as chance, but rather a part of the work itself. In reality, there are so many valuable people…A story by Borges says that the world was sustained by 11 fair men. Well I think there are many more and of course, women too, just people, without the gender.

Photographs provided by Alarcón Criado.