¿Cuál es nuestro hogar? (“What is our home?”), is one of the latest offerings from the Institut Valencià d’Art Modern (IVAM – the Valencian Institute of Modern Art). The exhibition, which will be on display until January 31, appears to be a reflection on the experience of isolation and confinement that has been a result of COVID-19.

However, as curator of the exhibition and director of the museum José Miguel G. Cortés explains, “it has nothing to do with the pandemic. It is a project that we have been working on for almost two years”.

In fact, its name is inspired by the 2003 installation “Where is our place”? which was created by Ilya and Emilia Kabakov.

The ¿Cuál es nuestro hogar? exhibition raises a debate about public and private spaces and is the result of a collaboration with Museo Nazionale delle Arti del XXI Secolo MAXXi in Rome.

Cortés explains that the project “was born out of an interest in establishing a link” between the collections of two of the most important cultural institutions in the Mediterranean region. As a result, visitors can admire twelve pieces in total – three from the IVAM’s collection and nine from the MAXXi.

You will find works by well-known creators like the aforementioned Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, Francis Alÿs, Jana Sterback, Bruce Naumann, Gabriele Basilico, Richard Hamilton, Teddy Cruz, Alfredo Jaar, Mario Merz and William Kentridge.

Twelve pieces to help you reflect on space

All of the pieces are very different form each other, but they all have one thing in common: they make you think about living spaces and social spaces; the city and the home, and the community versus private space.

“If there’s one central element, it’s that it all revolves around the link between public and private spaces and makes us realise that they are not two independent things. They complement each other and interact with one another”, explains the curator.

“Independent or neutral zones don’t exist. Actually, it’s totally the opposite. A good example of what I’m talking about is found in the different pieces and installations that are on display, because all of them construct stories, experiences, and narratives that act as a backbone for us so that we can feel and debate the many different types of spaces that are built every day”.

A sensory journey

The exhibit includes Fun House (1956), a playful and sensorial installation by Richard Hamilton that is an ode to consumerist society and the importance of cinema, and the iconic Triple Igloo (1984-2002) by Mario Merz.

The characteristic igloos of the latter make the observer walk through them and ask themselves about how architectural shapes and materials condition our daily actions.

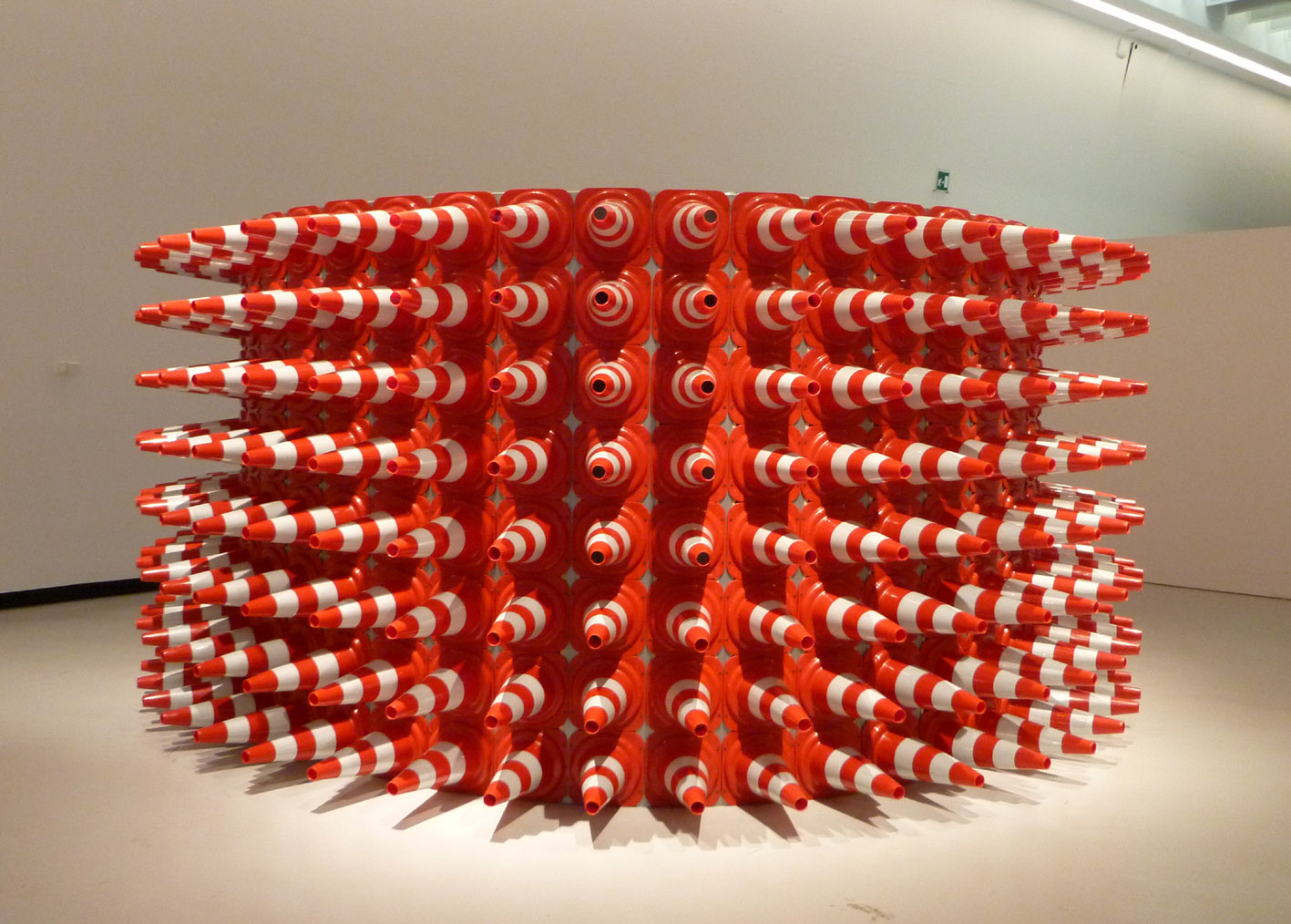

You will also find works that indulge in harsh political criticism, like that of architect Teddy Cruz. Cultural Traffic: from the Global Border to the Border Neighbourhood (2010) is made from more than 300 traffic cones that symbolise the idea of a border, be it a local or a global one, as a place of separation.

“Traffic cones, which are commonplace objects, stop us from getting close to the interior of the piece, turning them into a kind of weapon”, explains the director of the IVAM.

Empty cities

José Miguel G. Cortés says that all the pieces have many ways of being understood, but he firmly believes that after the experience of COVID-19, the installations will be interpreted in new ways.

“This is very obvious, for example, when it comes to the 150 photos by Gabriele Basicilo from the IVAM Collection. The photos show deserted European cities like Berlin, Madrid, and Milan at the beginning of the 2000s. There isn’t a single human being in the photos. Basilico constructed a type of artistic setting that didn’t have any spectators or actors – something that everyone recalls from the months in lockdown”.

The importance of light

The dozen installations that make up the exhibition are laid out in brightly lit rooms that contrast with other darker ones. In this way, light becomes an essential element in the creation of a space – the same way it is in architecture.

According to Cortés, lighting “helps us understand and highlights some of the more interesting aspects”.

Some pieces require more darkness and a more intimate or theatrical ambiance, while others, due to their dystopian character, need more intense light that highlights the piece against the walls of the museum.

When all the pieces are presented together, Cortés says they turn into “something that makes us ask ourselves what and where our home is. That is, if we even know what it is or if we have one”.